By Alissa Flores

A train horn blaring as it thunders down the tracks, the sweet aroma from the McKee Foods factory’s baked goods, and the bustle of community members and college students frequenting the small town are all prominent ideations when we think of Collegedale, Tennessee.

Yet there is much more to Collegedale than what we currently experience. An extensive and important story lies behind today's modern, growing community.

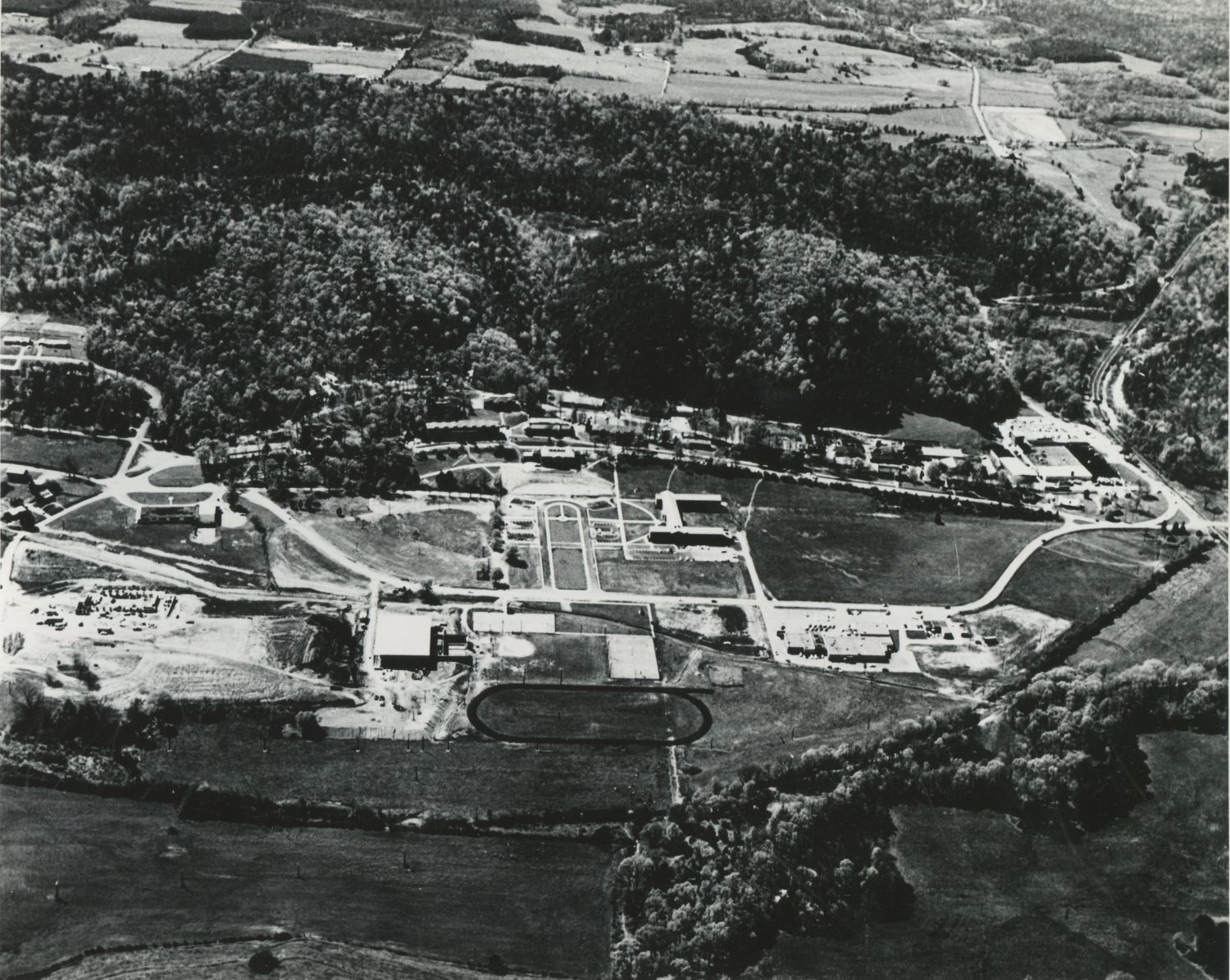

The landscape itself feels like an extension of history - once a rural farmland, now a thriving academic campus and town where the past and present collide in slow but steady progress. Cradled between the rolling ridges of Tennessee’s lush woodlands, Collegedale’s past directly intertwines with Southern Adventist University’s story, the McKee Foods corporation, and the Southern Railway, which have long existed.

Early Origins

Rewind to 1892. Professor George Alcord and his wife, Ada, kick-started a school called Graysville Academy in Graysville, Tennessee, according to Southern Adventist University’s history website. The first year at the Academy, enrollment reached a small number of 23 students. The small campus was composed of a boys' and girls' dorm, as well as an administration building.

According to Mills McArthur, a historian and history professor at Southern Adventist University, the administration of Graysville Academy wanted to be out in the country, away from the bustle of the town of Graysville. As classes took place and life continued at the Academy, there became a growing concern for the atmosphere for the students. On the outskirts of Graysville, a small suburb called Montague served as a mining community.

“I can only speculate on the specifics here, but evidently, there were all kinds of problems between the coal miners and the Adventists who lived in Graysville, with the very kind of rowdy and disruptive and just kind of a loose lifestyle,” McArthur said. “They did not want the influence of these coal miners. [They didn't want their students] to be corrupted by the loose morals of this mining group.”

In 1915, the women’s dormitory burned down. In addition to the dislike of being located so close to Montague, this was enough reason for the school to decide to move their location altogether.

“Well, we're going to have to rebuild anyway, at least one building. We don't like it here in Graysville, let's find a whole new campus. And that, in a nutshell, is how we end up here in our current location of Collegedale,” McArthur stated simply.

So, in 1916, Graysville Academy's remnants packed up, gathering their farm’s cows, chickens and wagons. They trekked the 25 miles to Thatcher Switch (now Collegedale), according to McArthur. At the time, Thatcher Switch was very unpopulated. The majority of the land, besides a small train station, was farmland owned by James Thatcher, a local farmer. In addition to the farm, Thatcher owned a limestone quarry.

“The Goliath Wall is not a natural cliff face—that was the old site of the quarry,” McArthur added.

The location was practically the site of a small company town. With the farm, quarry and the industrial work of the railroad, which transported the farming goods and the limestone the quarry expelled, Thatcher had a successful business venture. The workers lived in company-owned housing scattered among the ridgeline hills, and this created a self-sufficient community.

According to Southern’s historical website, Graysville Academy purchased the Thatcher land and began moving in, with 200 students turning away because of the lack of living space. With those who remained, the school changed names to Southern Junior College and began classes and construction on campus. The quarry was used to obtain some of the construction materials for the new buildings.

“For the first couple years that Southern is in college… They don’t have any dorms. They are literally living in tents,” McArthur expressed, sharing that the school used whatever resources they had available at the time but had hopes to grow in the future.

During the 1920s, progress began popping up around campus. Lynn Wood Hall, originally College Hall, was constructed and still stands on campus today. Despite forward movement in campus plans, the college was still struggling.

“There was talk of closing down the whole college within a couple years of making this move,”McArthur detailed the faculty’s sacrifice during financial hardship sharing the decisions some of the staff had to make during those tough first years. “We will forgo half our salary or just move into the dorm and just pay our basic living expenses,” McArthur said, summing up the sentiments of the college's pioneers at that time.

College Growth

In addition to the administrative sacrifice, the school added other activities, such as student labor programs, a broom shop, and the College Press, which helped students afford tuition. From the 1920s to the 1940s, the college grew, becoming an accredited institution and having enrollment reach records. In 1942, the college became known as Southern Missionary College, and by the 1960s, Collegedale started to become more of a community and less of just a university. The student population boomed after World War II, with returning GIs, but Collegedale remained primarily an Adventist community.

Mike Harrell, a Southern student from 1971-1974 and long-time resident, detailed his journey at Southern and witnessing Collegedale’s growth, “When I began attending [Southern Missionary College] back in 1971, it had a very small college, rural feel," Harrell said. "I felt separated from the city, and it felt a bit like a big family in the country.”

However, things really started to change in 1968 when the idea of Collegedale becoming incorporated as a city surfaced.

McArthur explained in his interview, “Why did the city want to incorporate in the first place? …Well, discussion was being carried on in Chattanooga through the newspapers about gradual annexation.”

Yet Adventists resisted the annexation to preserve their community and religious practices, but another reason was to avoid Chattanooga’s Sunday law.

The Chattanooga Sunday law prohibited certain businesses and corporations in that district from remaining open on Sunday. Because Collegedale was mainly a group of Seventh-day Adventists, who call Saturday their Sabbath, they wanted to veer away from that law.

Because of their decision, Collegedale ended up bringing in consumers from Chattanooga out to their businesses on Sundays because they were allowed to remain open, considering they were not under Chattanooga’s blue laws. While the city limits expanded, some areas refused to join Collegedale due to the large Adventist community.

“When I first came to the area, Collegedale had not long been an incorporated city,” Harrell said. “For the most part, the college was the town, and by far the majority of people living in the Collegedale area were affiliated in some way with the college.”

He continued to share that Collegedale seemed very separate from the city of Chattanooga, and that the community existed then primarily as a result of the college. Harrell has seen over time how the area’s population has grown and the university’s role has dramatically changed. According to him, many Collegedale residents have nothing to do with the university, and are not members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

With Collegedale now incorporated and beginning to build a name for itself, Southern became acknowledged as a four year university and finally switched its name to Southern Adventist University in 1996. As the 2000s rolled around, Southern reached new heights every couple of years, building additions to campus like the Hulsey Wellness Center and offering more programs for the gradual growth of students.

McKee’s Impact

Additionally, McKee Foods, which had been prominent in the area throughout the university's history, expanded its growth, which further contributed to the community by offering more jobs and traffic through Collegedale as they continued to expand, make additions and investments from 1952 through 2020.

Harrell detailed that as the bakery grew, it drew in more employees who did not attend the college. Additionally, McKee Foods increased the resident population that was not related to the University. Over time, the bakery also needed more advanced skills in its workforce, such as research nutritionists and engineers, which meant that McKees had to go outside the college and local area to find the skills it required as a large organization, according to Harrell.

“The volume of truck traffic required to ship McKee products nationwide has also significantly influenced the roads in the area,” Harrell stated. “Little Debbie Parkway is a good example, as well as the new expansion of Apison Pike. Overall, it seems that the bakery is respected and has been a positive impact on the community.”

While the emphasis of this research project is on Collegedale and its historical path, that path is directly intertwined with Southern’s. The university-generated human capital contributed to local government, business, and infrastructure.

“If you don’t have Southern there as the founder, maybe there is a town here… but it’s not going to look as nice as what we have,” McArthur said.

The history of Collegedale is one of tenacity, development, and a strong sense of self. What started out as peaceful farmland developed into a center of industry, education, and community. From its modest beginnings as a relocated academy to its development into a bustling university town, Collegedale's development was influenced by necessity, faith, and a dedication to independence.

“The community of Collegedale is larger, more diverse and more complex,” Harrell stated. “The University must now work harder to have a successful relationship with the local area. The physical footprint of Collegedale has become much larger, traffic has become much more congested and construction of all types is constant. Collegedale is no longer a sleepy, “bucolic” little rural location. There remains a unique environment to the Collegedale community and I don’t believe I can specify what that is, but it is there and makes the area a good place to be.”

Southern Adventist University's impact is still evident, both as a learning center and as the cornerstone upon which the town was constructed. Collegedale might not have developed into the community it is today without Southern, but instead, it remains an ordinary piece of farmland. Once bounded by farmland and railroad tracks, the area has evolved into a hub for business and education, but it has never lost its sense of origin.

*Information obtained from Southern’s History Website, Professor Mills McArthur, and previous Chattanooga Times Free Press articles*